Misconceptions on the Fighting in al-Suwayda'

Amid the ongoing fighting between pro-Syrian government tribal militias and local Druze factions in the primarily Druze province of al-Suwayda’ in southern Syria, it has become clear to me that misconceptions about the situation, promoted among media activists but also amplified by external analysts, have only exacerbated tensions and made the situation worse. I have been disappointed to see some of the latter in particular simply recycling crude social media talking points when they should be using their position to provide nuance that can hopefully contribute to a de-escalation.

1. The first misconception is the notion that the fight against Druze groups in al-Suwayda’ is simply a fight against ‘Hikmat al-Hijri’s militia/militias’ (Hikmat al-Hijri being one of the three mashayakh al-‘aql, or three most senior Druze spiritual leaders in Syria). This is misleading on multiple levels. To begin with, the Druze fighting the tribal militias are not simply the local Druze groups that declare that they are ‘followers’ of Hijri in the sense of supporting his political positions. Rather, Druze factions that disagree with Hijri’s positions and were more pragmatic about engaging with the government are fighting against the tribal militias too. The position was summed up well to me by Basim Abu Fakhr, spokesman for Rijal al-Karama (‘Men of Dignity’), which was talking to and coordinating with the Ministry of Defence prior to the escalation in al-Suwayda’: “We weren’t in agreement with Shaykh Hikmat al-Hijri, but we are fighting because of the violations of the invading forces and we are in a state of self-defence.” So also is Liwa al-Jabal (another faction that was more pragmatic about engagement with the government) participating in the fight, with the spokesman Ziyad Abu Tafesh (who told me prior to this escalation that he saw Hijri’s positions as unrealistic and an obstacle to a final status resolution for al-Suwayda’) now characterising the central government as the “terrorist Jowlani government.”

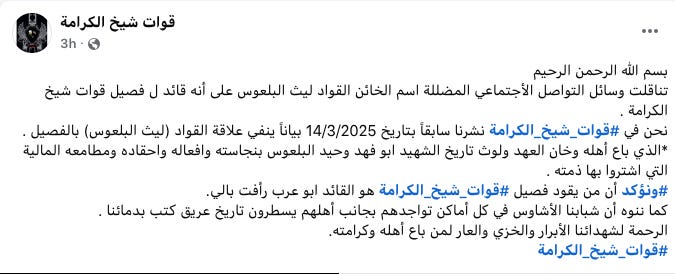

The main exception is Layth al-Balous, who, after initially hosting a delegation from the Ministry of Defence’s forces that entered al-Suwayda’, has now left al-Suwayda’. His own statement on events, which primarily seemed to blame Hijri for the events in al-Suwayda’, may be pleasing to government supporters and analysts sympathetic to the government but appears to carry little weight in al-Suwayda’. Indeed, the Shaykh al-Karama Forces, which originated as a pro-opposition break-off from Rijal al-Karama and is also fighting the tribal militias, has just put out a statement calling Layth a “traitor” in no uncertain terms (see below). For context, the Shaykh al-Karama Forces was at one point affiliated with the al-Karama Guesthouse run by Layth, but subsequently broke off and has declared support for Hijri’s positions.

2. Besides this point, the discourse about ‘al-Hijri’s militia/militias’ is itself problematic, giving a misleading picture of Hijri as being a militia commander participating in the battles and giving directives in the field. In reality, there are various Druze militias in al-Suwayda’ that are fighting the tribal militias and can only be seen as ‘affiliated’ with Hijri in the sense of proclaiming support for him and his ideals. For comparison, in Iraq, there are some groups within the broader ‘Popular Mobilisation’ (e.g. the al-Abbas Combat Division) that have particular affinity with Ayatollah Sistani, who issued the fatwa in 2014 that was seen as legitimating the rise of the Popular Mobilisation, and has himself given guidelines of conduct for military and security forces. These groups use rhetoric such as the ‘soldiers of the marja‘iya’ (marja‘iya being a religious authority) to describe themselves. Yet no serious Iraq analyst would characterise these groups as ‘Sistani’s militias’ or say that Sistani should be held criminally for any abuses they might commit. Rather, their affiliation depends on who actually commands them and their formal institutional affiliations. The same sort of observation also applies to the various tribal militias fighting in al-Suwayda’: these groups may proclaim loyalty to President Ahmad al-Sharaa but do not automatically become ‘al-Sharaa’s militias’ by mere virtue of that.

It matters to highlight this nuance because with the emergence of some evidence of abuses by some members of Druze armed groups against Bedouins in al-Suwayda’, Hijri is being portrayed as somehow engaging in and ordering these abuses and being criminally liable for them, when in fact he has always made clear that he rejects such conduct. If Hijri is criminally liable for those abuses, then surely the same logic must apply to al-Sharaa, who did not intend or wish for abuses to be carried out against Druze civilians in al-Suwayda’ by formal government forces (ministry of defence and ministry of interior) and tribal militias, but unlike Hijri, surely does have a formal liability in the sense of being the supreme commander of the Syrian state’s armed forces, as explicitly specified in the interim constitution.

3. The discourse about Hijri himself reflects a broader problem where political disagreements within Syria become distorted and inflated by exaggeration and hysteria in a way that fuels armed conflict and the risk of it. The foremost example of this problem, to my mind, is the characterisation of Hijri as a ‘separatist.’ I cannot speak for external analysts who are using this term, but it should be realised that within the Syrian context, the meaning is highly inflammatory as it is used to mean someone who is literally seeking to break off from Syria and form an independent polity, thereby betraying the country. For example, the term ‘separatist’ has been regularly used by supporters of the opposition to Assad and now supporters of the new government against the Kurdish-led ‘Syrian Democratic Forces’ (SDF), including as a justification of military action against the SDF.

But the truth is that there are no real ‘separatists’ in Syria right now, apart from some elements of a currently small-scale Alawite insurgency against the government, which use the moniker of ‘Coastal Shield’ and support the notion of a separate Alawite state as a possible option. In contrast, Hijri does not espouse the notion of a separate Druze state, just as the SDF does not espouse a separate Kurdish state. Rather, Hijri’s primary interest has been in securing a constitutional guarantee for a de-centralised and secular government as the basis for a final status resolution for al-Suwayda’. Members of Druze groups who were more willing to engage with the government- such as Liwa al-Jabal and Rijal al-Karama- might have had sympathy with these ideals but felt Hijri’s position was not realistic as a starting point for talking with the government: better instead, they felt, to be more open to dialogue and use that openness to engagement as a springboard for suggesting decentralisation at least. Personally speaking, I felt and still feel that decentralisation as a concept for governance in Syria is overrated. But it should be possible to sincerely disagree with decentralisation’s advocates (e.g. Hijri and the SDF) without accusing them of being ‘separatists’ and harbouring a sinister agenda against Syria.

Of course, the ‘separatist’ accusation against Hijri also stems from Hijri’s calls for international protection for the Druze, particularly in light of Israel’s airstrikes on Syrian government forces to prevent them from forcibly taking over al-Suwayda’ province. But one can criticise Hijri’s calls and what one may perceive as Israel’s recklessness without devolving into accusing him and his supporters of betrayal and treason. Hijri’s calls for international protection for the Druze amount to no more than that: calls for foreign protection against perceived threats to the community. They were not calls to form a Druze breakaway state from Syria, just as calls for international intervention to protect insurgent/opposition-held areas during the war with the Assad regime were not a call for separatism, and just as the SDF’s continued hope for American protection to guarantee the survival of the SDF and its ‘autonomous system’ is not a call for separatism.

4. Ultimately, if Hijri’s critics and the Syrian state want to prove that his calls for international protection for the Druze are unnecessary and mistaken, then the burden is on the Syrian state (which asserts the right to rule over Syria’s territory and people) to show that it can provide genuine security and safety to the population. Contrary to what government supporters are claiming, Hijri did not ‘sabotage’ the agreement with the government on the entry of forces affiliated with the Ministry of Defence and Ministry of Interior.

Rather, when the religious authorities, faction leaders and notables of al-Suwayda’ (including Hijri) issued a joint statement allowing for the entry of the Syrian government’s military and security forces, the government had an opportunity to show it could bring in its forces to al-Suwayda’ and impose security and order in a professional and disciplined way- the behaviour that we should expect of any state. Instead, the government’s own forces shot themselves in the foot by committing violations against Druze civilians, which is the entire reason why Hijri then came out with a statement saying the initial agreement had been imposed under pressure and called for the defence of al-Suwayda’ amid the ongoing violations. Hijri was the first to speak out, but other Druze factions soon joined the mobilisation for the exact same reasons. Liwa al-Jabal’s leader, for example, mentioned to me how at the same time discussions were taking place on initiatives such as forming joint patrols between local al-Suwayda’ factions and the internal security forces, violations were being committed by the government forces. He added that it is not acceptable for government officials to say nice things while the opposite is happening on the ground. Rijal al-Karama’s spokesman also considers that it was the government forces’ violations that led to the break down.

But even if we suppose that Hijri was somehow working to sabotage the agreement from the outset, the burden would still be on the government forces to show that they could act in a professional and disciplined manner when coming under attack from hostile elements. The buck stops solely with the government to prevent its forces from committing violations against civilians. Not only has it manifestly failed in this regard, but it has contributed further to the flames by allowing and commending mass tribal militia mobilisation as a pressure tool on al-Suwayda’, only adding to violations. No state that purports to uphold principles of rule of law should encourage or support such behaviour. But the reality also is that the government was either turning a blind eye to or perhaps even supporting similar acts prior to this latest escalation, with the repeated shelling of the peripheries of al-Suwayda’ by unidentified armed groups.

All this is a massive shame. In some discussions with some external analysts and observers who are highly suspicious of the new government (e.g. because of suspicions that al-Sharaa has not really shed his jihadist past), I have tried on the basis of my experiences in Syria to make them appreciate nuances that they might not have known about, so that they can realise that it is preferable to have critical engagement with the new government rather than adopt outright hostility to it as the starting standpoint: that is, engagement to help the country rebuild and prosper, but an engagement that does not turn a blind eye to internal problems and looks into issues such as the ideological direction being given to recruits into the new army and security forces.

And I still do believe that critical engagement with the government is the way forward, rather than measures like reimposing harsh sanctions or relisting al-Sharaa as a ‘terrorist’ when the country is in dire need for economic stabilisation and recovery. There are some minority communities in Syria where there is real security and the security forces behave professionally and respectfully (which I will discuss in more detail in a subsequent piece). Those examples are worth highlighting, not for the sake of doing propaganda for the government, but because we should care about the truth and show a productive path forward.

Nonetheless, it is simply not good enough for the state to have a good record with some minority communities while its forces and loyalist militias (tribal or otherwise) engage in extensive violations against other minority communities with little to no real accountability. This is why issues such as the coastal massacres of Alawites in March and the massacre and expulsion of the Alawites of Arza in Hama are crucial: not because Alawites or other minorities should be fetishised for being minorities, but because the victims of violations need to have answers about what the state is going to do to win their trust and ensure that these violations do not happen again. In the case of al-Suwayda’ too, there is now going to have to be a serious investigation into violations by government forces and tribal militias. Invoking ‘context’ or playing tu quoque won’t cut it: the state is to be held to the higher standard and must show it is the most responsible and trustworthy actor. And if one does insist on ‘context’, then why, in light of what has happened, would one not see how Hijri’s calls for international protection and sympathy for Israeli intervention have now surely gained far more currency within al-Suwayda’?

And finally, to external analysts and observers: I understand that many of you are driven by a sincere wish to see Syria recover and prosper after so many years of civil war and destruction, and reasonably want to give the new government a chance. But if you find yourselves essentially echoing crude social media talking points that are contributing to incitement and escalation of tensions within the country, please reconsider what you are putting out.

Your voice is badly needed Aymenn

With regards to Israel, the Druze called for their help out of desperation since they see MoD forces as an existential threat to them, yet Syrians were more than happy to label them traitors for it while willingly turning a blind eye to Al-Sharaa's own secret dealings with Israel and talk of joining the Abraham accords. This speaks volumes to how quickly the Syrian social media sphere turns against minorities.

Are people in this comment section smoking crack? Have they not seen the hours upon hours of evidence of Government forces, from Day 1, committing acts of brutal sectarian violence against the Druze of Suwayda? All the beheadings, lootings, red bands signifying their belonging to a unit of the Government, all the admissions from captured Jihadis, all the convoys from all across Syria proclaiming Jihad against the Druze, and the university students planning to rape and kill their Druze classmates? Are these people serious? Blaming the Druze for being a little reluctant to disarm and give complete authority to a crypto-Sectarian regime with absolutely zero leashes on its army of a million different ISIS splinters standing on each other in a trenchcoat.