A Sober Case for Learning Latin

Readers of this newsletter and personal friends have long known me to an enthusiast for Latin. I have produced Arabic and English translations of Latin texts, and occasionally write in Latin and translate longer texts into Latin for fun, continuing a passion since my youth. In general, I believe that more people should learn Latin, and I feel dismayed whenever I see news of universities potentially dropping Latin instruction.

However, enthusiasm for Latin should not mean support for all efforts to teach the language, particularly when such efforts are combined with promulgating blatantly false ideas and conspiratorial thinking. The same of course is true for any language learning. For comparison, I am also a literary Arabic enthusiast, and support teaching the language. If, however, I promote such learning with notions that people need to learn Arabic in order to learn the ‘truth about Islam’ in the face of a ‘politically correct’ (or conversely, ‘Islamophobic’) academy that supposedly wants to suppress this sordid or glorious truth respectively, there would be good reasons to question my enterprise. Similarly, I love Old English and the Germanic features of the language such as the strong verb ablaut patterns, but if I then promote instruction of the language on the basis that English people need to rediscover and emulate their ‘ancestral Germanic warrior culture and tradition,’ there would be legitimate grounds to raise concern as to whether I am trying to promote völkisch and Nordicist ideas.

A case in point with regards to problematic promotion of the learning of Latin is the popular X account under the name of “@latinedisce” (“Learn Latin”), which portrays the learning of Latin as some act of defending “tradition,” rejecting “modernity” and upholding some vague notion of “Western civilisation.” Alongside these very superficial and fetishising clichés, “Learn Latin” also suggests that universities today (supposedly in contrast with medieval universities) are no longer intended to “provide education and transmit knowledge,” and claims that the “academic world, dominated by woke professors, doesn’t want YOU to learn Latin. They aim to control the language to reshape the ancient world according to their modern ideologies.”

The reality of course is that “Learn Latin’s” notion of upholding “tradition” on the basis of learning Latin involves a high degree of selectivity as to what aspects of “tradition” should be celebrated. There is no harm in having an aesthetic taste for medieval art and architecture and Gregorian chant (I love all those things), or appreciating the value of medieval and classical Latin as historical records of the past (as I do). But it is also true that many Latin texts contain at least some ideas that few supposed ‘traditionalists’ would actually want to uphold today. For example, classical Latin texts generally presume the institution of slavery to be acceptable. A number of medieval Latin texts promote anti-Jewish sentiment, have outdated conceptions of the age of the world and world history, engage in practices that would now be considered unscholarly (e.g. imprecise citation and lifting from prior works without proper attribution) and promote absolute monarchy as the normative system of governance at odds with normative Western conceptions of democracy today. The question of what constitutes ideal ‘Western civilisation’ that is supposedly at stake invariably involves pick-and-mix, as well as a degree of arbitrariness as to what aspects of ‘tradition’ one goes with and what aspects one discards.

Perhaps more concerning though is the notion of a ‘woke’ academic conspiracy to suppress learning of Latin. To be clear: no such conspiracy exists. On the contrary, University departments that teach Latin need to have a continued intake of students year after year. Without students taking up the courses offered by those departments, those courses will generate no revenue, which in turn means that universities will no longer feel a justification to continue having those programs. True, the Classics academy (for example) has not been entirely free of ridiculous notions like the suggestion to drop the requirement to learn Latin and/or Greek as part of a degree course, and some students have attempted to impose stupid ‘woke’ ideas , but these problems are not reflective of the wider attitudes among academics who know Latin and use it for their research: in fact, they want people to continue studying the language, and for knowledge of Latin to be preserved and transmitted to succeeding generations. In so far as there is pressure against continued study of the language, the far greater problem stems from the wider academic crisis in which the study of humanities is no longer seen as ‘useful’ with a growing emphasis on STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

Unfortunately, the kind of audience that “Learn Latin” is attracting can be seen in the reactions to my calling out the account for giving the learning of Latin a bad name, although I did find the notion that I am Santa to be rather amusing:

More than ever, a sound, sober case needs to be made for the learning of Latin, far removed from crackpot political ideas. I would make the case for Latin in three simple reasons below:

1. Literary appreciation of texts in the original.

A number of Latin texts have multiple translations into particular languages. For example, Virgil’s Aeneid epic- which tells the legendary story of the origins of the Roman people and is probably one of the first Latin verse texts you will study in the original should you undertake a course in Latin- has dozens of English translations in prose and verse. These translations can be assessed in various ways in terms of their style, eloquence, idiomatic use of English etc., but in my view none of them can ultimately provide the same literary appreciation as reading the Aeneid in its original Latin, such as examining the use of metre, positions of words (with flexibility allowed because of Latin’s complex morphology) and other devices that may be difficult to replicate in translation.

To give a couple of very simple examples from Aeneid IV (which was the first Latin verse text I studied). Here the poet describes Queen Dido of Carthage’s longing for the poem’s protagonist:

illum absens absentem auditque uidetque

(“Absent from him, she hears and sees him in his absence from her”).

Here the repetition of absens in different cases and their juxtaposition arguably emphasise the present absence of the two from each other, and yet how close she feels to Aeneas (with the vivid imagery of him emphasised by the assonance of auditque videtque). Possibly also through the juxtaposition of absens in two different forms, the coming union between the two is hinted at- something that becomes clearer in a scene where the two have to flee a sudden rainstorm while hunting and then come into the same cave, where their ‘marriage’ takes place:

speluncam Dido dux et Troianus eandem

deueniunt

(“Dido and the Trojan leader come into the same cave”).

The phrase here is in fact almost identical with an earlier one in the poem in the form of words attributed to Juno, who promised to bring Dido and Aeneas together:

speluncam Dido dux et Troianus eandem

deuenient

(“Dido and the Trojan leader shall come into the same cave”).

Here the juxtaposition of Dido and dux (“leader”) emphasise the unity between Dido and Aeneas, and the almost exact same phrasing- the only difference being the shift of the tense from future to present tense: now what Juno said would happen is indeed happening.

I do not have space to go into further examples, but what is said here about literary of texts in the original equally applies to other texts that have been translated many times over, such as the Qur’an, which was translated partially and completely into Latin multiple times beginning in the 12th century CE and now has a huge number of English translations!

Linked to this point of course is that with knowledge of the original, you are free to produce your own translation of the text, regardless of how many times it has been translated before. See if you can produce your own translation that tries to replicate literary features of the original, or decide if you want to be faithful to the original or be freer in your approach. It is your translation to produce once you have a grasp of the original knowledge.

2. Texts without translation, and many avenues for research.

It is true that most of the surviving classical Latin literary heritage has at least one published and accessible English translation. One can thank the Loeb Classical Library for its efforts in this regard! Even so, the corpus of Latin texts goes well beyond just antiquity, and there are still many Latin texts that have no existing English translation or at least a readily accessible one- which makes the ability to read those texts in the original Latin all the more necessary. When I first embarked on translating Toledan archbishop Rodrigo Ximénez de Rada’s very important Historia Arabum (“History of the Arabs”)- a first-rate source for anyone interested in Western historiography of Islam and Arabs- into Arabic and then into English, I was surprised to learn that there has been no published English translation until now. This will change with my forthcoming translation and study of the Historia Arabum and the author’s other ‘Minor Histories’, to be published by Manchester University Press. Even so, the author’s massive Historia Gothica (“Gothic History”) and his contemporary Lucas of Tuy’s Chronicon Mundi (“Chronicle of the World”)- both important texts in the development of the concept of the ‘history of Spain’ and marking a transition point from Latin to the vernacular- do not have complete published English translations either.

It is not my aim here to present a comprehensive list of Latin texts that do not have a published or accessible English translation. In general though, it can be said that knowledge of Latin opens the possibility for you to pursue a large number of different avenues of historical and literary research. For example, perhaps you are interested in diplomacy between medieval Iberian monarchs and administrative? You will be advised to know Latin in order to read and translate large quantities of original documents. Or maybe you want to focus on relations between the Papacy and the medieval Iberian monarchs? Latin is essential then for reading relevant Papal bulls. The understanding and reception of the Qur’an in medieval Europe? You’ll need Latin to comprehend the Latin translations of the Qur’an and how authors used and responded to those translations. Early literary portrayals of Christopher Columbus’ arrival in the New World? There is a genre of ‘Columbus epics’ written in Latin! The history of the Western study of Middle Eastern languages like Arabic? It would be good to know Latin in order to understand early Western grammars of these languages and how they compare with the study of those languages today. Indeed, the first Western study focused on an Arabic dialect (Maghrebi Arabic) was written in Latin- presently I am translating it into English for a Jordanian publisher.

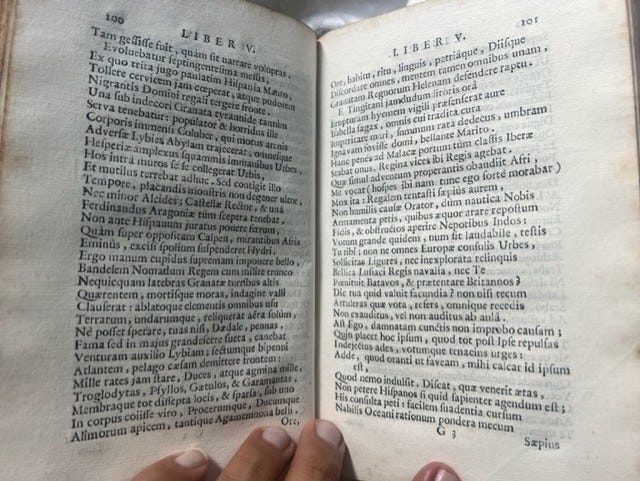

Excerpt from one of the Columbus Latin epics (from my personal collection).

The Maghrebi Arabic grammar I am translating, published in 1800.

3. Possible errors in existing translations.

Even if all Latin texts were translated, a lack of knowledge of Latin means wholesale dependence on translations, with no proper way of knowing whether the translations are wholly accurate. Once you get a very good grasp of the language, you may find that on closely examining an existing translation of the text, you disagree with renderings of certain phrases and detect unambiguous errors, and you may compare and contrast translations to see where they differ. The risk of error is all the higher when there are fewer existing translations and the original text presents a number of difficulties in interpretation. In a more convenient world, perhaps you could just pick up a Latin reference grammar like Gildersleeve’s work, thoroughly learn the morphology and syntax, and then zip through any Latin text. The reality though is more complicated, in that Latin texts can present obscurities of phrasing, and perhaps deviate from the rules you are used to knowing (especially true in the medieval era). Part of the thrill then of being a Latin scholar is giving these difficulties more considered thought, and being able to produce a rendering that is accurate and makes sense.

Consider the earlier mentioned Historia Arabum. Besides my Arabic translation published in 2022, the only other published translations were one in German (2006) and one in medieval Castilian (made available in a critical edition published in 2019). The original text, it has to be said, presents multiple difficulties, partly because of the author’s reliance in part of his work on a Latin source that is itself difficult (the eighth century Mozarabic Chronicle), and perhaps also because of bad translation of whatever Arabic source material the author was using- the latter suggested by Juan Fernández Valverde, who produced the modern critical edition of the text.

The German translation of the text was produced by Matthias Maser as part of his study of the Historia Arabum. That study is itself excellent and remains essential reading for anyone interested in the Historia Arabum, principally because the author showed that trying to identify specific Arabic sources Rodrigo might have used for his work is very difficult if not impossible, and that earlier hypotheses that had tried to identify this or that particular Arabic source faced objections that could not be explained away. Barring discoveries of new Arabic sources on Andalusian history that could shed further light, it is only safe to say in a general sense that Rodrigo made use of Arabic source material. In short, Maser’s work was a good example of showing where scholars had to show humility and be more cautious in their assertions.

However, the German translation he produced of the Historia Arabum has some deficiencies, some of which I discuss in my forthcoming work. Consider the following phrase in the original text:

illis diebus quatuor Hayram fautoribus in conflictibus male cessit

Maser’s translation is: “Hairan ließ in diesen vier Tagen seiner Anhänger in übler Weise mitten im Kampf im Stich” (“In those four days, Khayran badly abandoned his followers in the middle of the fight”).

The medieval Castilian translation is different: “En aquellos días quatro, lo pasaron mal los favorizadores de Hayrán en las batallas” (“In those four days, Khayran’s supporters had a bad time in the battles”).

Clearly, it is not possible for both of these translations to be correct. One or the other is more accurate. The latter translation is in fact the more accurate one. It is of course only possible to know this with knowledge of Latin. The verb cessit is not governed by the word ‘Hayram’ as its subject but in fact forms an impersonal phrase in male cessit, with the person affected in the dative case- an established phrase in Latin literature (so e.g. mihi male cessit, which can be translated idiomatically as “the situation went badly for me”). In other words, what the text is in fact saying is that “in those four days, things went badly for Khayran’s supporters in those battles.”

To be clear, the above example is not an exercise in gleefully finding errors of others and pointing them out in an attempt at public humiliation. Rather, the point is that scholars and translators are human and can make mistakes in interpretation and translation of texts. I myself have always been open to the possibility of making errors and am more than happy for someone else to identify and correct them. The phenomenon of peers being able to review and correct each other on mistakes in translation and interpretation, or resolve difficulties in Latin texts, is only possible if we have people continuing to study Latin. As far as I am concerned then, the more the merrier.

Conclusion

As can be seen, there are sound, scholarly reasons for the continued teaching and study of Latin, none of them requiring a superficial fetishisation of ‘tradition’ and ‘Western culture’ or a form of prejudiced ‘Occidentalism’ that trashes anything associated with ‘the West’ as inherently ‘racist’ and unworthy of nuanced appreciation. Much of what has been said above about the study of Latin is equally applicable for the study of other languages that have bequeathed a substantial literary corpus, such as Arabic.

Should you be interested in learning Latin after reading this post, then you are more than welcome to contact me personally about the matter. In the meantime, I can also recommend some academics on the realm of social media who also help to promote the continued study of Latin, all of them more serious scholars of Latin than I will ever be: Georgy Kantor, Barnaby Taylor, Armand D’Angour, Llewelyn Morgan (unfortunately not on X anymore, but check out his blog here), Bret Devereaux and Victoria Austen. More generally, do look into the continued outreach by the University of Oxford (where I initially studied) and other universities. There really isn’t a conspiracy to suppress Latin instruction! We just want Latin taught well and without promoting blatant misconceptions about the field of academic study of Latin!

A great article. I never liked latinedisce, who uses Latin as a propaganda tool, constantly advertises, winks at the public and slavishly flatters "blue checks".

It is a genuine pleasure to read an article displaying not only your erudition but also your emotional attachment, your love of Latin and other languages, and your enjoyment of your beloved scholarly pursuits.