Richard Dawkins and 'Cultural Christianity'

Apologia Pro Richard Dawkins?

An interview clip with Richard Dawkins on LBC in which the prominent atheist declared himself to be a ‘cultural Christian’ is presently doing the rounds on social media. Expressing dismay at the promotion of Ramadan instead of Easter in Britain, Dawkins noted that if he had to choose between Christianity and Islam, he would choose Christianity every time.

These remarks have provoked a wave of outrage and surprise. “There's something deeply ironic about Richard Dawkins, who spent decades undermining Christianity, now saying he is a ‘cultural Christian’ who ‘likes living in a Christian country,’ and is ‘horrified’ to see Islam rising in Christianity's place,” proclaimed one editor. The ‘luxury communist’ thinker Aaron Bastani similarly wrote: “Bizarre from Dawkins, who wrote a book called ‘The God Delusion’ claiming religion was a deeply malevolent, dividing force in the world. Now he’s calling himself a ‘cultural Christian’? Find it odd to use religion to extend your secular political points.” Murtaza Hussain of The Intercept accused Dawkins of shifting his position after participating in a “ruthless cultural war against Christianity” and only “belatedly” realising his mistake. Even the prominent historian Tom Holland, who seems more understanding of Dawkins’ perspective, is under the impression that Dawkins has only recently begun to shift his views.

If only people’s memories went beyond the latest clip to go viral. The reality is that Dawkins’ advocacy of ‘cultural Christianity’ over Islam is nothing new or bizarre, and to accuse him of having waged a ‘cultural war’ on Christianity is off the mark. I observe this point because I distinctly remember reading Dawkins’ 2006 book The God Delusion back when it was first released.

To be clear, I do not agree with Dawkins’ general portrayal of religion as something fundamentally harmful. In my view, so long as you do not have religious beliefs that involve coercing or harming others simply for not sharing your beliefs (here’s looking at you, Islamic State members and supporters), or religious beliefs that can endanger the health of oneself or others (e.g. denouncing vaccines of importance for general human health), then there is no problem.

However, I am more sympathetic to Dawkins’ point that proclaiming yourself to be a believer in a religion generally involves believing a set of propositions to be true. For example, if you are a Christian, then you believe that Jesus is the Messiah, that he died on the Cross for our sins, and was resurrected. You should then ask yourself on what evidentiary basis you might hold a religion’s set of propositions to be true, and then make a decision as to believing in them or not. In other words, if, say, you do not believe there is evidence to support the claim that Jesus is the Messiah, then you should not call yourself a believer in Christianity. If you do not think evidence supports the idea that Muhammad is the final prophet of God, then you should not call yourself a believer in Islam. It is on this basis that I respect (for instance) my friend Sohrab Ahmari’s conversion to Catholicism. Sohrab was not converting out of some identity pose as a ‘champion of the West’ and claiming that his adopting Catholicism constituted ‘defending Western civilisation.’ Rather, he took the time to study and consider the religion in-depth, and decided that it was true. Similarly, when a friend of mine expressed concern that marrying his Muslim romantic partner might mean having to convert to Islam, I advised him not to convert unless he actually believed in Islam’s claims. The end-result of his not converting was, in my view, happier for both him and his significant other, as they had a very enjoyable wedding day that celebrated both of their religious heritage traditions.

All this aside, Dawkins was clear in his book The God Delusion that, at least in the Western context, not believing in Christianity should not mean disregarding or forgetting the role Christianity has played in shaping Western culture and civilisation in particular. One section that stood out in my mind when I read the book was entitled “Religious Education as a Part of Literary Culture” (pp. 340-344) where Dawkins proclaimed he was “a little taken aback at the biblical ignorance commonly displayed by people educated in more recent decades than I was.” Dawkins then drew specific attention to the King James Version of the Bible for containing “passages of outstanding literary merit in its own right,” while adding that “the main reason the English Bible needs to be part of our education is that it is a major source book for literary culture. The same applies to the legends of the Greek and Roman gods, and we learn about them without being asked to believe in them.”

Regardless of what one thinks of Dawkins’ views on Christianity, Islam or religion in general, there is no denying the validity of his point here. As he notes, Biblical references permeate English language expressions and literature. By extension, he notes (correctly), that knowledge of the Qur’an is important for better appreciation of Arabic literature. Dawkins then underlines that “an atheistic world-view provides no justification for cutting the Bible, and other sacred books, out of our education.” Even further, he argues that “we can retain a sentimental loyalty to the cultural and literary traditions of, say, Judaism, Anglicanism or Islam, and even participate in religious rituals such as marriages and funerals, without buying into the supernatural beliefs that historically went along with those traditions.”

As should be apparent, what Dawkins wrote here is completely consistent with his claims elsewhere to be a ‘cultural Christian,’ and I do not see anything outrageous or shocking about it. Of course, some of Dawkins’ critics will argue that one cannot have it both ways in advocating against religious belief while wanting to retain the cultural heritage bestowed by a religious tradition, but I do not see Dawkins’ position as necessarily untenable. I must admit that Dawkins can claim some credit for inspiring me to take a greater interest in the King James Version and read it from start to finish during my teenage years. The other main inspiration was my piano teacher. Unlike Dawkins, he is an unapologetic Protestant, but both Dawkins and my piano teacher made me realise the literary merit of the King James Version and the Bible’s wider cultural importance, and I too wish that there were wider appreciation for the King James Version in particular among English speakers. One does not have to be an Anglican to have such sentiment. I also say this as someone who now prefers to read the Bible in its original languages and in Latin translation (and the Septuagint Greek version for the Hebrew Bible), rather than English translation.

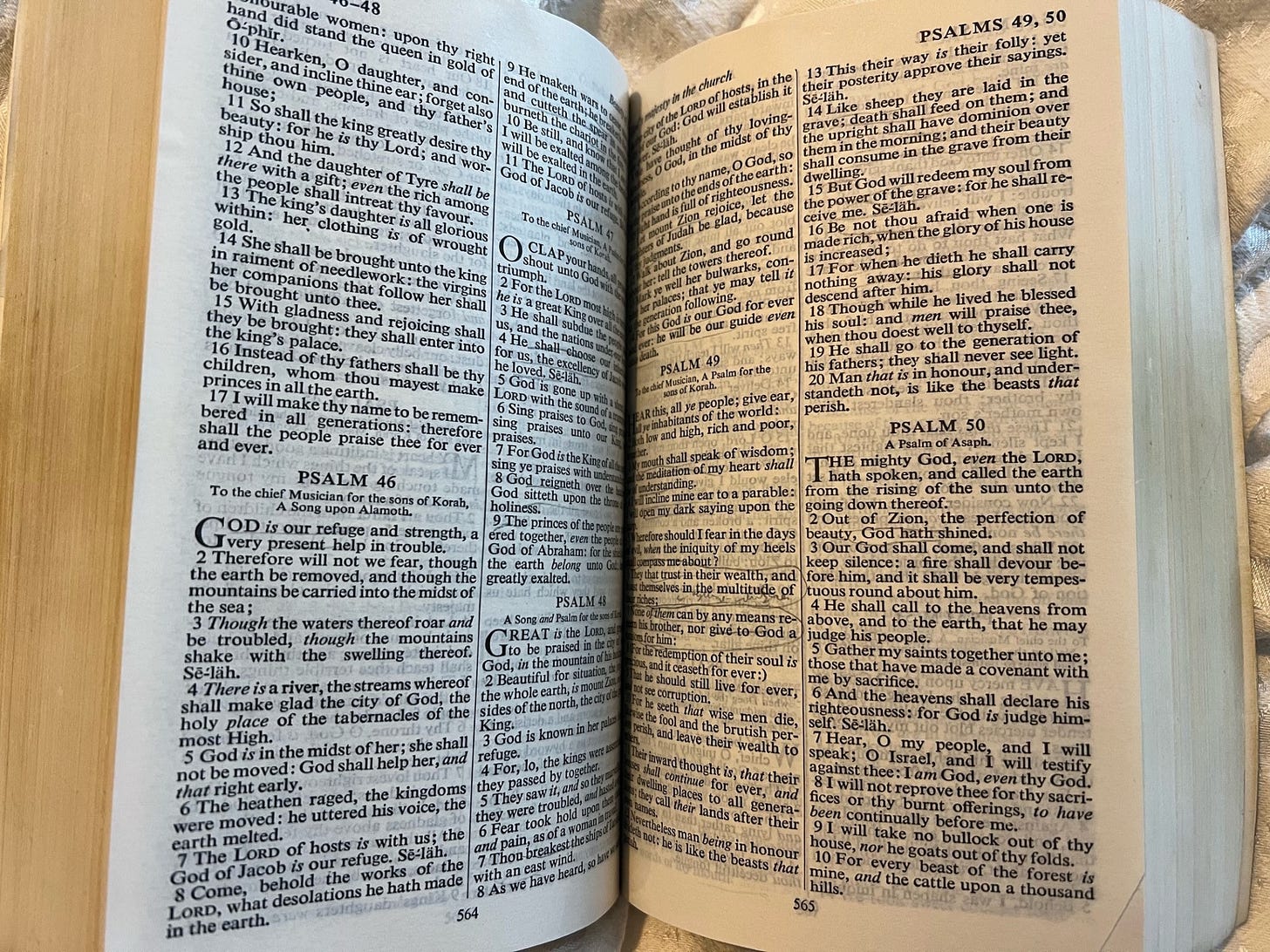

My copy of the King James Version, which I read in my adolescent years.

Pencil underlinings and annotations in my King James Version.

Dawkins’ view of Islam as being a worse religion than Christianity is also not anything new. In 2010, for example, he described Catholicism as the “second most evil religion in the world”: the clear implication being that in his view Islam is the worst religion. I have no interest in getting into a comparison between Christianity and Islam, but I am more understanding of Dawkins’ concern about the decline of maintenance of Christian cultural heritage. As a simple comparison for illustration, consider the wider region of the Middle East and North Africa. Much of its cultural heritage has been fundamentally shaped by Islam. Let us then suppose that a tidal wave of atheism and/or other religious beliefs swept the region, leading to a large-scale decline in belief in Islam. Would it be a welcome sight then to see conversions of old mosques and other Islamic cultural heritage buildings into bars, restaurants and housing, along with large-scale construction of modern church buildings as the new centres of worship, the decline of study and knowledge of the Qur’an, and the end of any celebration of occasions like ‘Id al-Fitr and ‘Id al-Adha? One of the sadder sights to behold in Britain is the conversion of churches into bars, restaurants and housing. I would not want to see something similar happen to mosques or shrines in Iraq or elsewhere in the Middle East or North Africa, and I would not want to see something similar happen to the cultural heritage of the region’s established non-Muslim religious minorities. Put more generally, it is unfortunate if new trends in religious belief (atheist or otherwise) lead to destruction and forgetting of prior cultural heritage bestowed by long-standing religious tradition or traditions.

In short, Dawkins’ remarks about being a ‘cultural Christian’ and advocating for Christian cultural heritage are really not as new, controversial, weird or contradictory as they are being portrayed on social media. Perhaps examining and considering his output beyond a short video clip would have made more people realise that.

The problem with everything-Dawkins (as I see it) is that he appears to be the epitome of the egotistical academic who is bright, but not nearly as bright as he assumes himself to be. Often, their so-called "intelligence" is apparent only with regard to their deep-diving into a speciific, often very narrow, subject of academic endeavour, success in which leaves many academics with the assumption that they are thereby very well equipped to pronounce on any of a huge variety of other subjects, leaving one to wonder if any of them actually understand what REAL ":intelligence" is.

I see the Dawkins mentality as an extreme example of such a faulty assumption.