Qur'anic Studies and the Early History of Islam

Interview with Marijn van Putten

How far can the traditional narratives about the emergence of a particular religion be considered to correspond to historical reality? This sort of question is especially relevant for religions in the more distant past such as Judaism, Christianity and Islam.

By now, there is a huge amount of research in the field of Biblical criticism, which explores Biblical texts from a variety of angles such as textual criticism (trying to determine the original text based on surviving manuscripts) and source criticism (trying to determine sources for those texts) and then the wider question of the historicity of the narratives contained in those texts. The corresponding research approaches in Western scholarship to Islamic texts- in particular, the Qur’an- have been seen as lagging behind Biblical studies, but I think there is a potential to mischaracterise the field. That is, it might be assumed by some that the study of the early history of Islam is marred by ‘political correctness’ and a fear of offending Muslims that prevents scholars from being too bold in questioning the origins of Islam. Such an impression, for example, was reinforced by the publication of ‘The Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Koran’ under the pseudonym of ‘Christoph Luxenberg’ in a bid to protect against reprisals.

Having perused research in this field for over a decade, I do not think that this conception of a field stifled by deference to Muslim sensibilities is an accurate impression, and I do not think there was a justification for ‘Christoph Luxenberg’ (whoever that person is) to write under a pseudonym. In fact, the study of the Qur’an and early Islam is a very dynamic and exciting field, and has produced a wide range of views on debates about historicity. Some scholars (such as Nicolai Sinai, author recently of a dictionary of key terms in the Qur’an and under whom I took a course at Oxford during my undergraduate years) accept that the Qur’an can largely be explained by the traditional narrative of its origins in terms of a preacher called Muhammad who spent a part of his prophetic career in Mecca and part of it in Medina, thus dividing the text into traditional ‘Meccan’ and ‘Medinan’ suras (chapters). Of course, adhering to this view does not necessarily mean accepting the notion that the Qur’an is the literal word of God and the validity of Islam’s claims as a religion: it is rather simply a judgement that the narrative of Muhammad’s life in terms of its events is broadly true, independent of whether one actually believes him to be a prophet as he claimed. Others have gone so far as to postulate that Muhammad did not exist and that the Qur’an emerged and was fixed over a much long period of time. Between these two poles is an extensive spectrum of opinions.

A potential risk when researching or observing this field is to be led by an emotive bias: that is, either wanting to believe Islam is a true religion, or wanting to believe it is false, and then effectively proceeding on the basis of trying to prove what one wants to believe. This risk is by no means confined to study of early Islam. It can also be seen in discussion of early Christianity, where many atheists (for example) espouse the notion that Jesus never existed. I personally do not find the mythicist hypothesis about Muhammad to be at all convincing for similar reasons why I do not find the mythicist hypothesis about Jesus to be convincing: in my view, there is good historical evidence for their existence that comes from not too long after their deaths, and that evidence is independent of one’s religious beliefs about them. Espousing the notion that Jesus and Muhammad did not exist may sound superficially avant-garde and ‘rational’ because of its radical skepticism, but it does not make for good history, which is about trying to determine what actually happened in the past, independent of emotive biases.

To give general readers an overview of where present research is at with regards to the study of the Qur’an and the history of early Islam, I present a written interview with my friend Marijn van Putten, a Dutch linguist who focuses on Qur’anic Arabic. I believe that Marijn and I first encountered each other in 2019 when I translated a chapter of the Qur’an into Gothic, the earliest Germanic language attested in substantial literary form. The interview is slightly edited for clarity.

. Tell us a little about yourself, how you came to study of the Qur'an, and your main research interests at present?

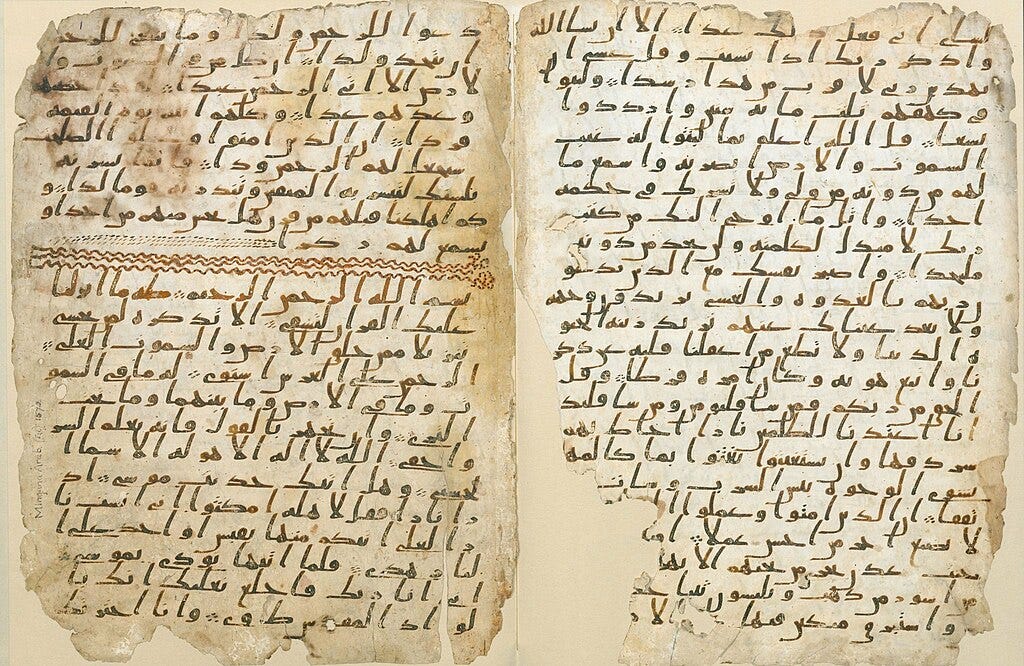

I'm Marijn van Putten. I'm a historical linguist/philologist concerned with the history of Arabic and the Qur’an. Besides this I also do research in Berber linguistics. I came to study the Qur’an due to the exciting developments that were taking place in the history of Arabic. While Arabic is a major world language, its linguistic history is profoundly understudied, and on top of that its earliest piece of literature had hardly been subjected to linguistic study at all. This is why I came to focus on the history of the Qur’anic text, the language of the Quran and its reading traditions. My current research project is concerned with the reading traditions of the Quran: How did the earliest Muslims decide on how precisely to recite the Quran? What competing options were there? And how did the seven (and later ten) canonical readings end up becoming the canon?