In Memoriam: Abd al-Majid Sharif

A true free Syrian voice

For some idealists, the Syrian revolution that toppled the Assad regime is about freedom for all Syrians within a national vision devoid of sectarian identity politics: not an artificially enforced unity that rejects cultural and religious diversity, but rather a vision that can celebrate this diversity while ensuring that all Syrians can feel a sense of belonging to the homeland. Moreover, for such idealists, the revolution does not seek to just replace one regime with another that is to be the object of sycophantic adoration by the masses, but rather should enable freedom of expression and the right to criticise so that proper, substantive debate can be held and mistakes can be corrected.

My friend Abd al-Majid Sharif, who was from the originally Druze village of Kaftin in the Jabal al-Summaq area of north Idlib countryside and recently passed away, was for me someone who always embodied this idealistic vision of the revolution. It may be that the proportion of people inside Syria who adhere to this vision is relatively small. Whatever the case, the vision embodied by Abd al-Majid and other principled figures remains very much worth advocating for.

Abd al-Majid was born in 1952. He studied mathematics and became a mathematics teacher though he subsequently left the profession and migrated to Venezuela for a period (1994-2003), working as a truck driver to deliver goods to shops. According to what he told his relatives, he was subjected to robbery a number of times in Venezuela at the hands of criminal gangs.

He subsequently returned to Syria and was among those who supported the 2005 ‘Damascus Declaration’ issued by various opposition figures. Looking back on that declaration, the warnings contained therein about the disaster that Syria was heading towards under the Assad regime and its totalitarian policies sound prophetic. The reforms called for in that declaration- and which Abd al-Majid endorsed- were not based on sect-centric politics, but simply called for opening up the country under a democratic system and equality for all Syrians regardless of religion and ethnicity. This then was the basis of Abd al-Majid’s opposition to the regime: not a belief that the regime marginalised Druze or other sects in favour of Alawites, but rather simply that it was a dictatorial system that deprived its people of basic freedoms taken for granted by many in Western countries.

Abd al-Majid remained firm in his principled opposition to the regime and it was on that basis that he supported the uprising against the regime that began in 2011. Admittedly, within Kaftin and the other Druze villages of Jabal al-Summaq, there was some reluctance among the inhabitants to come out in favour of the uprising, but Abd al-Majid was keen to get them more involved in the uprising. Abd al-Majid’s family paid a price for his activism: one of his children was arrested for a short period, while a daughter of his was summoned for questioning at the university where she was studying.

But Abd al-Majid did not relent in his opposition to the regime, and as regime control over much of north Idlib countryside disintegrated in 2012-2013, he established a local council in Kaftin. This local council became affiliated with the opposition-in-exile’s Syrian interim government, even as the Jabal al-Summaq area came under the control of Jabhat al-Nusra (the precursor to Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham- HTS) by 2015. As part of its consolidation of control over the region of Idlib and its environs, HTS sought to subsume the local council of Kaftin and all localities in Idlib under its control via its General Services Administration, subsequently folded into the HTS-backed “Salvation Government” project that was announced in November 2017. As a result, Abd al-Majid resigned from his position as head of the local council, replaced with a new HTS-backed local council that was itself subsequently dissolved as part of a structural change in which larger municipal offices would be responsible for services in multiple villages.

One of the most admirable things about Abd al-Majid was his willingness to speak out (regardless of whether one agreed with him or not), even at the risk of upsetting HTS and the wider opposition to the Assad regime. For example, he came out firmly against the attack by Turkey and Turkish-backed insurgent factions on the Kurdish-populated enclave of Afrin in 2018, decrying how “our rifles have become for hire.” Similarly, he declared his opposition to all foreign fighters participating in the war in Syria (including foreigners who had joined HTS) in the following terms in 2021: “If you reject one of the three groups [foreign Shi‘a fighters on the side of the regime, foreign PKK cadres or foreign Sunni fighters] without rejecting the other two, you are not against terrorism and no one should take you seriously. Patriotism means we reject every foreign fighter on our land and this applies to the intervening armies, and practically speaking, if none of the sides wins the battle militarily, there is no solution except for the simultaneous departure of all of them.” Similarly, in the summer of 2022, he directed an open message to HTS and its leader Abu Muhammad al-Jowlani (Ahmad al-Sharaa) warning of “daily acts of harassment by Turkistanis” (Uyghurs and other central Asians) against the people of Qalb Lawze (one of the villages of Jabal al-Summaq) and calling on HTS to deploy an armed force to deter the acts of harassment. Finally, in 2024, in an interview with me regarding the protests in Idlib and its environs against HTS rule, Abd al-Majid denounced what he saw as HTS’ monopolisation of power and marginalisation of independent institutions that could check its authority, and that HTS was not suitable to be part of a solution (though he also criticised the demonstrations for having some unproductive slogans against Jowlani/Sharaa).

Even after the fall of the Assad regime, Abd al-Majid did not go the way of some who previously criticised HTS and Sharaa and then turned into bootlickers and mouthpieces. Rather, he stuck to his principles: namely, the belief in a state based on equal rights for all Syrians, not a sect-centric vision or one based on distributing positions based on sect to meet box-checking quotas. As he put it in January: “The pluralism that we want does not mean positions for the people of a sect, but rather means the right for the Syrian citizen to have the position he is suited to, regardless of his religious identity or ethnicity.” Similarly in late March, having already declared that the interim constitution did not represent him (clearly because it grants the president broad powers), he called for “a real national dialogue that draws up an agreed-upon social contract among all the components of Syrian society and its political forces, with the departure of foreign fighters, armies and bases from our land. Without this, Syria will not be united and sovereign.” Similarly, he criticised the way the new army and security forces were being built, calling for the removal of “unsuitable militia leaders who have a bad reputation, and foreigners whom we do not accept as the leaders of our army: [we need] a national army, not a global jihadist army, partisans and corrupt people.” At the same time, he was also keen to emphasise the need for reason and calm in dialogue and debate, asking in the same period: “Why do you curse and make accusations of betrayal when you read something that goes against your opinion? Did we not say that we are a revolution of dignity? So how can you attack the dignity of someone who holds a different opinion? The one who doesn’t respect the dignity of others has no dignity himself.”

It is possible that Abd al-Majid’s consistent expression of his principled opinions made him the target of ire and was the reason behind an attempt to assassinate him not long before his death, but the party behind the assassination attempt has not been identified. Although Abd al-Majid survived the assassination attempt, he sadly passed away on 9 August in Idlib, following a long struggle with lung cancer.

I cannot help thinking that the present situation in Syria would be much better if Abd al-Majid’s vision for Syria held greater sway among the ruling authorities. What we have instead is an administration that in many ways continues the strengths and shortcomings of the original HTS project in Idlib and its environs: successful at emphasising Syria’s place in the order of nation-states and establishing relations with regional states and international powers, but an internal vision of governing Syria that monopolises power in the hands of the president and his clique and is Sunni Arab-centric, with the building of security and military forces on similar sect-centric foundations rather than an inclusive national vision that enforces law and order without discrimination. What Syria needs right now is not internal and external observers engaging in sycophancy and apologetics for the new government’s shortcomings in the name of ‘realism’, but rather more people like Abd al-Majid willing to speak up on principles and advise the government as to where precisely it is going wrong.

Abd al-Majid’s political positions aside, I was always honoured to consider him a friend, having interviewed him multiple times. In addition, Abd al-Majid was always supportive of my academic work, including my translations of medieval Iberian literature. I will dearly miss him.

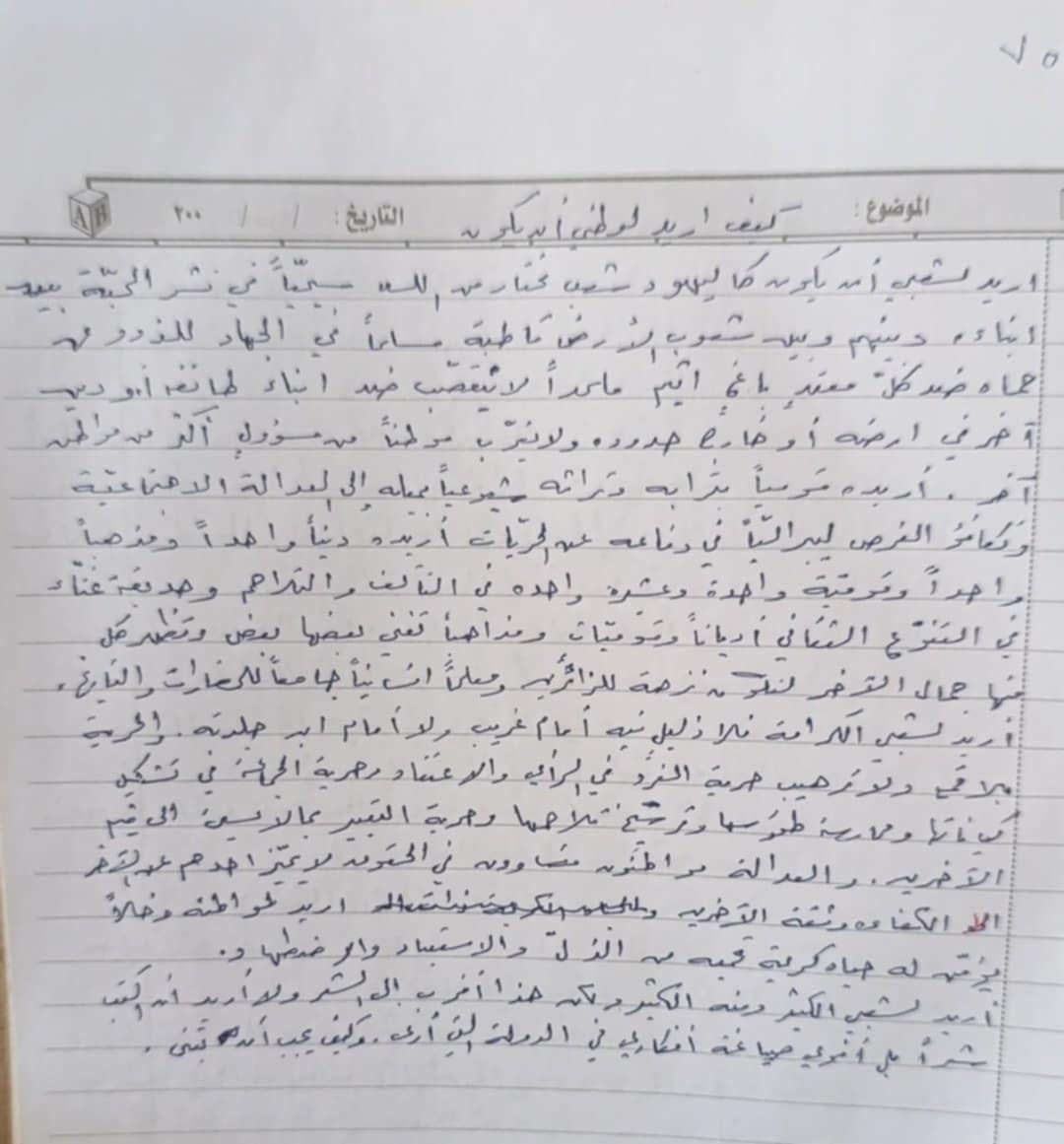

To conclude, I leave you a hand-written note he wrote some years ago that summarises his vision for Syria and its people, together with my translation of it:

What I want my homeland to be

I want my people to be like the Jews: a people chosen by God; Christian in spreading affection among the people of their religion and among the peoples of the entire world; Muslim in waging jihad to defend their abode against every sinful transgressor; atheist in refraining from partisan rage against the people of another sect or religion in their land or outside their borders, and not favouring one citizen over another in the eyes of an official.

I want my people to be nationalist in their soil and heritage, communist in their inclination to social justice and equal opportunity; liberal in their defence of freedoms. I want them to be one religion and sect and one ethnicity and one tribe in mutual affection and solidarity, and a reach garden in cultural diversity in terms of religions, ethnicities and sects, enriching each other and showing each other’s beauty, so that we can be an attraction for visitors and a humanitarian teacher that brings together civilisations and history.

I want my people to have dignity with no humiliated person among them before a foreigner or someone of their own, and to have freedom without repression or terrorisation, for the individual among them to have freedom of opinion and belief, and for my people to have the freedom to come together and form their groups, and to practise their rituals, and implant mutual solidarity and freedom of expression, which does not harm the values of others and fairness.

I want my people to be citizens who are equal in their rights, with no discrimination between one or another, except in competence and the trust of others. I want the citizen of my people to have an income that guarantees him a dignified life that protects him from humiliation, servitude and persecution.

I want much for my people and much from them, but this is closer to poetry and I don’t want to write poetry but rather intend to forge my ideas in the state that I envision and how it should be built.

Abd al-Majid Sharif.

Thank you for sharing this. It is of course the best kind of vision that Abd al-Majid Sharif expressed to you and through you. Syria is again being steered off course. The UAKBO money deal shows how, in a different dimension, money is talking while internal dissent is being suppressed and sectarianism endorsed. Alas, after some 600,000 dead, sectarian slaughter continues enflamed by neighbours and international players alike...