Climate Change, Water and Conflict in the Middle East

A Response to Climate Scientist Michael E. Mann

As the world continues to experience global warming caused by carbon dioxide emissions from human activity, there is legitimate concern as to how climate change is impacting and will further impact the availability of fresh water resources in the Middle East, which may be impacted by higher temperatures, reduced rainfall and reduced snowpack in mountainous areas. Besides this impact of climate change, there is also legitimate concern about continued population growth in the region and mismanagement of water resources. In turn, these issues generate speculation about the possibility that climate change and/or water scarcity may be a contributing factor to existing and future conflict in the Middle East.

While it is entirely legitimate to raise these matters, scientists and observers should also avoid exaggeration and overstatement. It is unsound to suppose that climate change and water scarcity are somehow the fundamental/underlying cause of conflict in the Middle East in general. Yet it is analysis somewhat along these lines that was offered recently in an op-ed at The Hill by Michael E. Mann, one of the world’s most prominent and high-profile climate scientists. In particular, two assertions stand out from Mann’s op-ed. On a more general level, he approvingly cites the deceased Israeli-American agronomist Daniel Hillel as arguing that “conflict in the Middle East, while nominally over land disputes, has always fundamentally been about the battle for water.” On a more specific level, he argues that “the underlying cause” of the unrest and subsequent civil war in Syria was a “decade-long drought.”

To be clear, I think Mann’s work on climate change in general is important, particularly with regards to his pushback against a growing trend of ‘doomerism’ that engages in exaggeration and suggests it is somehow too late to do anything to mitigate climate change and its effects. In fact, all mitigation that goes towards adaptation and reduces carbon emissions towards net zero is better than inaction, and this is so even if the world exceeds the thresholds of 1.5 or 2 degrees Celsius of global warming.

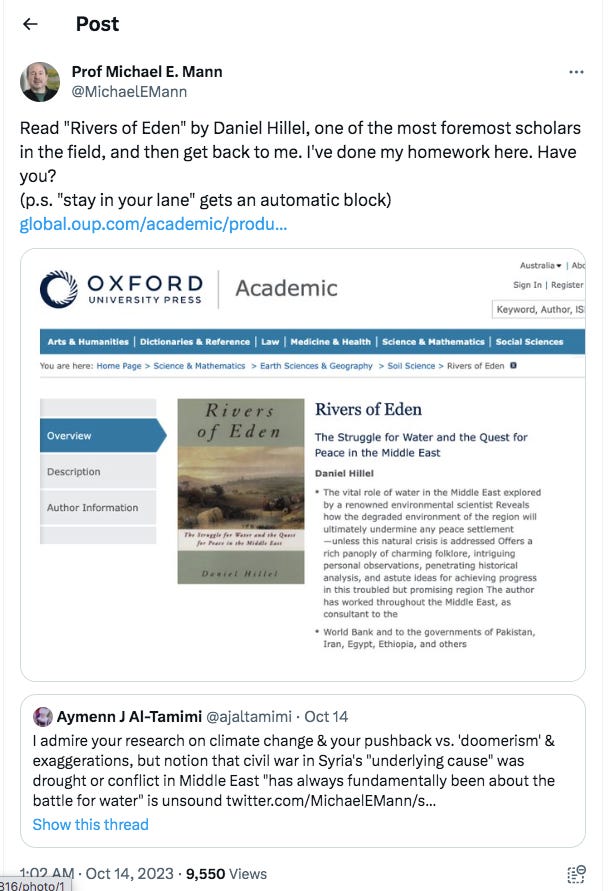

Regardless of my broader agreement with Mann, I take issue with both of the assertions highlighted above from his op-ed. When I pointed out my disagreement on the application X, Mann’s response, unfortunately, was rather gratuitous, as can be seen below.

Rather than respond to Mann immediately, I decided to take him up on his call to read Hillel’s book Rivers of Eden, which was published in 1994 (just after the Oslo I Accord but also prior to the Israel-Jordan peace treaty) and can be accessed here. What actually became clear is that the book does not support Mann’s characterisation of Hillel’s argument. To claim, based on this book, that Hillel argues that “conflict in the Middle East, while nominally over land disputes, has always fundamentally been about the battle for water” amounts to a significant misrepresentation of the book’s contents.

Rivers of Eden’s Actual Contents

What Hillel argued in his book is that environmental degradation in the Middle East is an “important dimension of the Middle East’s fundamental predicament” (p. viii), and a dimension that had been neglected in analysis. As Hillel’s book makes clear , this degradation importantly includes misuse of water resources, but it also comprises other aspects such as overgrazing and deforestation. Thus, Hillel suggested that in the course of the Middle East’s history, “often, the cause for strife has been rivalry over scarce and abused resources: farming and grazing lands, and- in particular- access to water” (p. 6). This clearly does not mean that ostensible land disputes in the region have always just been disputes over water. Control of land might crucially include control of important water resources, but that does not automatically make water the fundamental aspect of a land dispute- only a potential important part of it. Land in itself, regardless of its water resources, can be an important holding.

Certainly, Hillel argued that environmental degradation is a “primary cause of the people’s frustration,” and that the Middle East is in need of “a bold program of economic, social and environmental rehabilitation” (p. 18). Yet he also made clear from the outset of his book that “the problems besetting the Middle East today are multifaceted and exceedingly complex. Ethnic, national, religious, economic, social and historical conflicts combine to make the present scene contentious” (p. vii). In other words, Hillel was ready to acknowledge that conflict in the region took on multiple dimensions, and he did not simplistically argue that water disputes were really the fundamental issue behind all of them.

Indeed, going deeper into Hillel’s book, it becomes evident that the author notes and discusses many different conflicts that have occurred in the Middle East’s history. Nowhere does the author suggest that all these conflicts were fundamentally about a ‘battle for water.’ Examples mentioned by Hillel include the Assyrian conquest of the ancient kingdom of Israel, the wars between Judah and Babylonia, Alexander the Great’s campaign against the city of Tyre in Phoenicia, the Roman-Jewish wars, the Greek and Roman conquests of Egypt, the Arab conquests of the Middle East, conflict between Saladin and the Crusaders, the Mongol invasion of Iraq and destruction of Baghdad, Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, the First World War, the Arab revolt against the Ottomans and conflicts and tensions in the aftermath of the First World War, the tensions between Arabs and Jews in Palestine (e.g. the 1920 riots, the 1936-1939 Arab revolt in Palestine) culminating in Israel’s war for independence in 1948, and the First Gulf War.

For example, how does Hillel explain the Arab conquests of the Middle East in the seventh century CE? He in fact goes with the very traditional explanation that they were conquests motivated by the Arabs’ new Islamic faith and obedience to the “call to jihad” in the sense of holy war against infidels (p. 72). In other words, Hillel accepts that these conquests were motivated by religion and the desire to expand the domain of Islam. It is not the point here to discuss the validity of this interpretation, but simply to note that Hillel does not argue or suggest that the conquests were fundamentally motivated by water scarcity among the Arabs and a desire to seize the conquered’s water resources.

Similarly, how does Hillel explain the Jewish-Arab tensions that culminated in the 1948 war? According to him, the large-scale Jewish migration into Palestine “encroached upon an existing community of Arabs, disrupted its culture, and threatened its own aspirations” (p. 149). Hillel further adds: “As the Arabs saw it, they were being forced to sacrifice their birthright for the sins of European anti-Semitism, for which they were not responsible,” culminating in the Arab rejection of the UN partition plan for Mandatory Palestine and the Arab war against the Jewish state (p. 150). Again, it is not my purpose here to discuss whether Hillel’s analysis is right, but simply note that nowhere does he claim that these events were basically a conflict over water. Rather, his narrative is that the conflict here was fundamentally about an Arab perception that Jewish immigration and suggestions of a Jewish state infringed on what they believed to be their rightful sovereignty and dominion over the land. This conflict over sovereignty and dominion is deemed to be at the root of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict today (pp. 292-94).

In some instances, Hillel discusses how conflicts might involve use of water as a weapon of war (e.g. Saladin’s victory over the Crusaders by denying them access to water, the targeting of Iraqi and Kuwaiti water assets in the First Gulf War- pp. 265-66), but that is not the same as saying that those conflicts are fought over water resources, and the tactic of water deprivation in war is hardly unique to the Middle Eastern context, as Hillel himself noted with examples beyond the region.

The meat of Hillel’s book is the discussion of five important water resources in the Middle East: (i) the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, (ii) the River Nile, (iii) the River Jordan, (iv) the rivers of Lebanon and (v) aquifers. In these sections, Hillel does give examples of disputes and conflicts that have emerged or could emerge over these water resources: for instance, tensions between Iraq and Syria regarding Euphrates river flow when the Syrians filled the Tabqa Dam reservoir in 1975 (pp. 108-109), the potential for future dam projects in Ethiopia to affect supply of water to the Nile downstream in Sudan and Egypt (p. 138), how conflicts over diversion of water from the Jordan “precipitated a series of armed confrontations with Israel, which contributed indirectly to the war of 1967” (p. 163), violent protests by Lebanese Shi‘a in the early 1970s against plans to divert water from the River Litani to meet Beirut’s growing water demand (p. 184), and Israel’s control of water supplies in the West Bank region and how it impacts Israeli thinking on retaining control of territory and yielding sovereignty to the Palestinians (pp. 208-209). Yet from none of these instances can one infer that Hillel thought conflict in the Middle East has always fundamentally been a ‘battle for water.’ Rather it is just becomes clear that water can be a factor in some conflicts and tensions in the region.

The remainder of Hillel’s book is primarily devoted to practical suggestions about dealing with water scarcity in the Middle East, including suggestions for better water management, augmenting water supplies through schemes such as greater use of desalination and water transfer between countries, and criteria for countries to share water resources. For Hillel, the “water problem and peace process are inextricably intertwined,” but the Middle East also faces a host of problems including disparities of wealth, thwarted national aspirations, disputed borders, religious fanaticism, terrorism, ethnic civil wars, and “megalomanic dictators,” with an marked rise in Islamism fuelled by the perceived failures of the “secular ideologies of nationalism and socialism,” a nostalgia for the past glory of Islamic civilisation, and a rage against the West that introduced secularism and “supported corrupt regimes” (pp. 280-81). Ultimately, Hillel suggests:

“Peace has seemed elusive because the basic cause of the suffering remained unrecognized and unaddressed. That root cause, I submit, is the destruction of the region’s traditional way of life, brought about by the twin onslaughts of ill-fitting modernization and environmental degradation, exacerbated by the population explosion” (p. 282).

And thus what is needed is a comprehensive program of “economic development and environmental rehabilitation.”

Agree or disagree with Hillel’s broader analysis, he certainly was not suggesting that conflict in the Middle East has always fundamentally been about the ‘battle for water’ as Mann would have it. Rather he was saying that good management of water resources and establishing good cooperation between regional countries over use of water (certainly desirable things) would be important aspects of realising peace and stability in the region, but he also recognised that the region was bound with many political complexities over power struggles and national, ethnic and religious identity groupings.

If it feels as though I have dwelt on Hillel’s book at length, it is really just to show to Mann that I have indeed done my homework on it, and his representation of the book’s argument constitutes a distortion of its contents. Yet unlike some of Mann’s critics on his broader arguments about climate science, I will not accuse him of lying. Perhaps something got distorted in the editorial process, or maybe he had not read the book in a while and misremembered its contents.

Even if I had found though that Hillel really did argue that conflict in the Middle East has always fundamentally been about ‘the battle for water,’ the claim would not have been valid simply because Hillel made it. There are many examples of conflicts in the region, both past and present, that cannot be plausibly characterised as fundamentally being about fighting for water. For instance, consider the First Crusade that inaugurated the era of the Crusader states in the Levant that lasted nearly 200 years. What was the fundamental drive behind it? Was it not a desire to impose Christian sovereignty on the Holy Land at the expense of Muslim sovereignty? Or, turning to the present day, consider the conflict in northern Syria between Turkey and the U.S.-backed ‘Syrian Democratic Forces’ (SDF). There have been multiple reports about Turkey using water scarcity in that region as a weapon against the SDF (e.g. here), but no one claims that the conflict between the two sides is fundamentally about water. Rather, it is well recognised that the root of the conflict is Turkey’s view of the SDF as an extension of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, which has been waging an insurgency against Turkey in the hope of establishing some form of Kurdish autonomy or self-rule within part of Turkish territory- a goal rejected by Turkey. In other words, the conflict is one over ethnic/nationhood aspirations and Turkey’s perception of terrorist threats to its national security.

These are just two random examples, and depending on how granular one wants to go in terms of examining conflict in the Middle East, the number of other examples running counter to the generalisation can be multiplied exponentially. I am afraid that if Mann wants to maintain the view that conflict in the Middle East has always fundamentally been the ‘battle for water,’ he is going to have write a comprehensive history of the region that covers a period of thousands of years (and perhaps spanning tens of thousands of pages), while utilising all kinds of source materials and archival research, in addition to showing an ability to conduct primary research in a range of languages. Needless to say, such an undertaking would be beyond the capabilities of a single researcher. But in any case, the view is untenable. It very patronisingly diminishes the importance of human ideas behind conflict, whether embodied in differing national, political, religious and ethnic identities, or in the pure lust for dominion and power. These impulses are not unique to the Middle East, but rather universal in nature.

The ‘Climate Change-Syria War’ Narrative

What about Mann’s more specific claim that “the underlying cause” of the unrest and civil war in Syria was drought? Here, too, I am afraid, his statement is a misrepresentation of the source material he cites. His two main sources are a 2015 paper by Collin Kelley et al. on the drought and then a Mashable article on a study about drought variability in the Mediterranean over the last 900 years. Neither of these two studies, nor any of the other studies (see a recent bibliography here) that examine the question of the link between the drought/climate change and the unrest and civil war in Syria, go so far as to claim that the drought was the underlying cause. Rather, it is only suggested that the drought, which is argued to have been made more severe and/or likely because of climate change, was one of multiple contributing factors to discontent prior to the unrest and may have made the unrest more likely, in that it is argued that the drought led to a substantial internal migration of people towards urban areas in the west of the country, putting strain on resources, housing, job opportunities etc.

Indeed, Kelley was clear in representing the 2015 study to the media: “We’re not arguing that the drought, or even human-induced climate change, caused the uprising.” Similarly, in response to criticism by Selby et al. of what was seen as the weak evidence adduced in support of the narrative about the link between climate change and the unrest/civil war, Werrell and Femia noted: “The drought was one of a number of other environmental, economic and governance factors…contributing to the mass displacement of a significant number of Syrians, and thus potentially increasing the “likelihood” of conflict – a probabilistic, not a causal, claim.”

While the suggestion of the drought being made more likely by climate change and the positing of the drought as a contributing factor to some discontent prior to the uprising are not unreasonable, the notion of the drought as the underlying cause of the unrest and subsequent civil war is not only a distortion of the literature but also problematic in itself, because such a narrative overlooks what should be very clear to anyone who has studied the history of the Syrian conflict in detail.

Quite simply, the Syrian government represents a dynastic political system that many Syrians evidently opposed prior to 2011. These Syrians either did not openly express their opposition to it, or did so and were subjected to repression for doing so. For some, opposition to the system was primarily based on the fact that it was seen as denying basic freedoms like proper democratic elections and freedom of expression. For others, the system was seen as un-Islamic and led by a sect (the Alawites) denying the Sunni Arab majority of the right to rule. For many, the system was seen as marked by corruption, and had not brought about new economic prosperity and improvements in livelihoods. Whatever the precise focus of opposition in various people’s minds, the government, unlike some of its regional neighbours further south in the Gulf, did not have huge amounts of cash from fossil fuel revenues to buy people’s loyalty. Once it was seen how uprisings had sprung up and brought down the rulers in Tunisia and Egypt, there was a clear knock-on effect as part of the wider ‘Arab Spring.’ Many Syrians who had actually been opposed to the government now sensed it was time to cast off the fake displays of loyalty or simple acquiescence, and started to come out and protest. This is a far more compelling and obvious narrative than the claim that drought was the underlying cause of the unrest and civil war. I should also add that no serious observer of the war or those on the ground would argue that the war has ever fundamentally been a battle for water.

There are some other specific criticisms to be made of the ‘drought-uprising’ narrative. For example, as highlighted in a more recent study by Eklund et al., it is not clear that the drought triggered an ‘agricultural collapse’ or large-scale migration of a more permanent form, but rather the migration was one more temporary in nature. Second, despite criticisms of some of Selby et al.’s arguments, there is force in what they say when they note that there is a lack of good evidence of a prominent role for migrants from the northeast (which was worst affected by the drought) in the initial unrest, and there is likewise a lack of good evidence that demands or grievances surrounding migrants and the problems they might have brought about featured in the protest movements.

Conclusion

In the end, it may be asked whether these issues regarding the accuracy of Mann’s claims and his misrepresentations of source materials matter. Yes, they do matter. On a more general level, Mann is a prominent communicator on a key issue with a large social media following, and thus the stakes are particularly high for him to be accurate in his statements. To put it another way, with great prominence comes great responsibility. Exaggerations and misrepresentations, as documented above, will lead to suspicion that he is committing errors in, say, some of his messages that try to reassure people that things can still be done about climate change, in a time that Mann has termed a ‘fragile moment.’ I would like to emphasise again that I am not accusing Mann of deliberate misrepresentation. Still though, I am disappointed in how short he has fallen in his op-ed in terms of representing his sources and the conclusions to be drawn from them regarding the two issues discussed in this article. I was also disappointed by the tone of his response to me, and expected better of him. As a specific note to Michael: I never suggested you should “stay in your lane.” If a climate scientist can make accurate observations about the Syrian civil war, conflict in the Middle East or medieval Latin literature (for example), then no one should object simply because the person is a climate scientist. If, however, you make inaccurate claims and misrepresent source material in support of those claims, then expect to be called out on it.

More specifically in relation to the issues discussed however, generalising conflict in a region to essentially being a battle for water has the potential to give rise to bad policy. For instance, if third parties seek to mediate disputes between actors whose conflict is not fundamentally a dispute over water resources, it is unlikely that those third parties will have any success in their efforts to mediate. In effect, those mediators would be telling the actors in conflict with each other: ‘Yes, yes, yes, you say your grievances and issues are X, Y and Z, but we know that what you’re really fighting about is water.’ This could only come across as patronising and arrogant to the actors in conflict, who would no doubt feel they are not being listened to. Similarly, overemphasising an event that may have been made more likely by climate change or overemphasising climate change in general as the underlying cause of a conflict can lead to bad policy, in that actors who have pursued poor policies that have helped foster grievances and conflict may be let off the hook, as they can claim that their actions made no difference to the situation in contrast with climate change that is beyond their control.